When Yang Chengfu was teaching in Shanghai in the 1930’s, he taught his students ten essential principles needed to perform taiji properly. I’m going to describe these ‘Ten Commandments’ and talk about how to practice them. First, though, it’s important to know that incorporating these instructions and internalizing them takes time and attention. Holding all ten in your mind at the same time is impossible at first. I’ll introduce some exercises to help us chain two or more of the essential principles together. With time a transformation takes place. Gradually the ten principles will become second nature. We make them so much who we are, that not doing them would take some real effort.

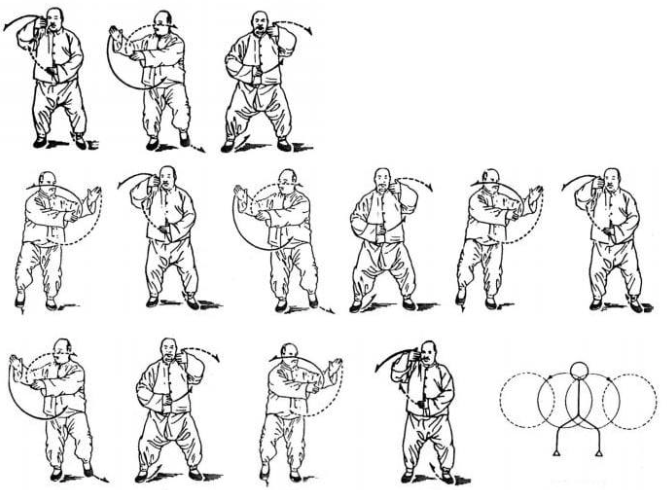

The ten principles are:

- Crown of the head up (Xu Ling Ding Jin)

This sounds like the instruction you often hear in many types of movement: the head up as if suspended from above. But Yang Chengfu apparently meant something different from this. The four characters he used – or rather his student Chen Weiming used them (Yang may have been illiterate) mean ‘Empty, lively, pushing up, energetic’. There’s been a lot of debate about exactly what he meant by this. The head must certainly be upright, and there should be a feeling of liveliness at the crown. But one shouldn’t use strength to lift the head. This would make the neck stiff. Remember that the crown is not the middle of the skull; it’s the highest part of the head, a little farther back. Raising the crown involves bringing the chin back slightly. Let the ‘spirit of liveliness’ lift the crown of the head. Perhaps the single word ‘buoyancy’ is enough to remember.

- Hold in the chest, round the back (Han Xiong Ba Bei)

This action is and must remain quite subtle. The idea is that the chest shouldn’t be puffed out. Retracting the sternum somewhat, and slightly rounding the back has the effect of allowing the center of gravity to sink to the dantian: the important central point of the abdominal cavity. If you try it, you can see that this is a double-edged sword: it could also lead the qi upwards, and reinforce the stretch towards the crown of the head. This will draw your center of gravity upwards, so you should be especially aware of dropping the qi down. When you practice these first two principles together, there’s a feeling of stretching from the lifted crown of the head, down to the center of the abdominal cavity. This forms the vertical axis for all our movement. Rather than talking about the center of gravity, taiji teachers usually say to allow the qi to sink down to the dantian.

Exercise – Underwater walking

Here’s an exercise to help us combine points one and two. We’re walking underwater, someplace where the water is clear and warm, just about body temperature. You can feel the buoyancy of your head, so to keep your bare feet on the sand, you need to point downwards with your breastbone. This will keep you from floating away. Once your feet are grounded, let’s do the arm movements of ‘wave hands like clouds’ as we turn to the left and the right.

- Relax the waist (Song Yao)

Here is a very simple Chinese sentence. Just two words. Song the Yao. Song is one of the most important ideas in the taiji canon. It means relax or release, but never implies collapse. In talking about Song Yao, Yang often said that the ‘waist is the commander of the body’. The yao that he talks about here is the area between the lower ribs and the hips and especially the lumbar spine. The waist is the critical link between the upper body and the legs. A good general piece of advice in martial arts is that if you notice a lack of power in your techniques, look to the waist. This is because, as Yang Chengfu says elsewhere, power is generated in the feet, conducted upwards by the legs, steered by the waist and is expressed in the fingertips. So if your power isn’t reaching all the way to your hands, the problem may be the linkage from the legs to the upper body.

Releasing the waist means allowing it to be flexible, but it also refers to the release to gravity. In other words, allow more room to exist between the lumbar vertebrae. This will allow the weight of the upper body to drop into the legs.

- Distinguish between empty and full (Fen Xu Shi)

Simply put, in taiji we always have more weight in one leg than the other. There’s always a polarity of empty and full, or emptier and fuller. The empty/full difference generates the yin-yang which drives all the movement.

Here’s an example. If you’re standing in bow stance, with seventy percent of your weight in the left leg, the whole left side of your body, including the torso, will feel different from the right side. Even when you are striking with your right fist, your left side will feel denser, more compressed and more substantial. The right side of the body is thus free to expand, and it’s as though your fist is striking because the right side of your body is expanding. Each joint from your right heel, knee, hip, shoulder, elbow and wrist opens a little bit, bringing the fist closer to its target.

Exercise: (more underwater walking) – the Sand Crab goes for a stroll

In the first exercise we pointed downwards with the breastbone, to bring qi down to the level of the abdominal cavity, all the while feeling buoyancy and vitality at the crown of the head. Now we want to shoot the qi all the way into the feet. Let’s take a repetitive action, like the crabwalk leftwards in ‘Wave hands like clouds’, but leaving the hands out for now. Just fold your hands in front of your stomach. Turn the waist to the right to close the right kwa (groin, inguinal fold) and, releasing the lumbar spine, pour your whole weight into the right leg. Imagine pouring sand into a pipe. Your leg is that pipe. At a certain point you’ll be able to lift your left leg without any leaning. That means your left leg is empty and your right leg is full. Step left with the empty left leg, and as you turn left, pour your weight into it, pointing all the time with the lumbar spine in the direction of your left foot. We’re doing two things at once: releasing the Yao and distinguishing empty and full.

- Sink the shoulders and weigh down the elbows (Chen Lian Zhu Zhou)

Sinking the shoulders and pointing downwards with the elbows helps us not to ‘float’ as we move. We should always feel a connection between the shoulders and the feet. Therefore, we sink the shoulders until we can feel their weight in the soles of our feet.

This is a good moment to sum up the essentials up to now. The first five points are all about posture and rooting. The head’s movement is upwards. Drawing the qi down with the sternum, releasing the waist and sinking the shoulders and elbows all bring the center of gravity downwards. Doing these actions together gives a wonderful stretching sensation. Differentiating empty and full shows us the path along which we’re bringing our weight to the ground: more in one leg than the other. In taiji this is in fact called ‘the ground path’.

During my first lessons with my teacher, with whom I later did my certification training, he showed me that I was blocking at the knee, and not allowing weight to travel to the ground. He’s an architect and can easily spot a load-bearing wall – or knee, for that matter.

- Use intention, not muscular force (Yong Yi Bu Yong Li)

Li is force due to muscular contraction. Yi means intention. We lead the qi using intention. This helps the body to stay released (song) and the joints open. This way our movements can be quick and supple. Relying only on muscular strength causes our movements to become clumsy and inefficient.

It may seem as though taiji tries to substitute some mystical force for muscular strength, but that’s not true. Taiji aims to develop a faster, stronger and more agile power than what is available in ‘external’ martial arts. By mastering principles one through five we are in optimal contact with the ground. Our weight pressing into the ground creates an equal and opposite upwards force: the Ground Reaction Force (GRF). If we find the perfect alignment and keep the joints open and muscles relaxed, we can use this upward force. When Yang Chengfu says that ‘power is generated in the feet, conducted upwards by the legs’ and so forth, it’s the GRF he’s talking about. Get good at this and you can bounce people across the room with it. As your partner pushes into you, they’re in fact pushing against the ground.

7. Coordinate the upper and lower body (Shang Xia Xiang Sui)

We practice moving all the parts of the body as a coordinated whole. Here we’re talking about grounding, receiving the GRF through the feet, and coordinating its movement through the six main joints of the body: ankles, knees, hips, shoulders, elbows and wrists. And of course issuing this force successfully through the hands into our opponent. The other way of saying this is that the upper body follows the lower. First the grounding, then you can lead the qi upwards.

8. Coordinate internal and external (Nei Wai Xiang Ge)

Taiji is an internal martial art. This means that one continuously feels the filling and emptying, opening and closing – on the inside. These internal sensations are the causes of which the external movements are the effects. What goes on inside a taiji practitioner changes over time. The best example of this is peng, a very real feeling which nonetheless takes many years of practice to cultivate. I’ll go into it in some detail in another article, but for now we can just call it ‘expansion’. It’s also the name of the posture ‘Ward Off’. If you have it – that feeling of internal expansion, you know what I’m talking about. If not, keep practicing. It’s worth it.

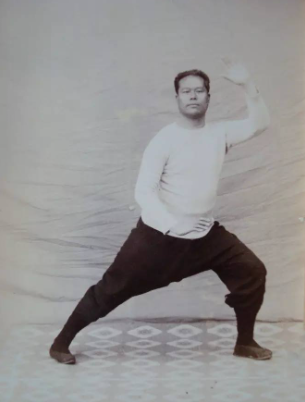

Here we see Yang Chengfu’s Ward Off posture. It’s not only that extending his arms, he will have felt an internal expansion as well. As we become more Song, the GRF opens the joints and pushes more and more on our connective tissue, especially within the torso. So we really begin to feel like a balloon on the inside.

Yang Chengfu got rather fat in his later years, so that was a certain type of expansion as well. Not peng, however.

9. Move continuously without any interruption (Xiang Lian Bu Duan)

Sometimes when doing the taiji form we seem to stop, but even then there is internal movement, invisible from the outside. Two images used by Yang Chengfu were a mighty river, and silk thread. When winding silk from the cocoon of the silk moth, one must keep a steady speed. Jerky movements will break the thread, and stopping will cause the thread to stick. Silk reeling is a much used image in taiji – also when it comes to joint-locking.

10. Find the stillness in the movement (Dong Zhong Qiu Jing)

Practicing taiji allows us to find tranquility while exercising. Yang Chengfu compared taiji practitioners with performers of other kung fu styles. He pointed out that other martial artists become tired from all the athletic jumping and kicking. Practicing taiji slowly and mindfully allows us to improve our breathing, to become supple and relaxed, without becoming tired.

One more exercise: an (press)

Stand in a bow stance with the right foot forward. Weight at first in the left leg. Sink into the left leg, then move forward and sink into the right leg. Close the right kwa. Crown stays up, and use the rooting action of the sternum (and rounding the back), releasing the yao, sinking the shoulders and weighting the elbows. If all that is working, you may feel the upward GRF threading through your right leg and hip. Perhaps you can feed that all the way into both hands. Rinse and repeat. Then try this with a partner. Don’t push – don’t use strength, and see what happens.